'Deep Space Nine' made me feel like I wanted to die. It also gives me hope.

Twenty years ago, "Far Beyond the Stars" introduced Star Trek's first black captain to America's ugly, racist past. This year, it helped me process my own mental health in America's present.

With a wind chill of 4˚ below zero, it was supposed to be the second-coldest New Year's Eve we'd ever had on record, and I was indoors, under a blanket. Somehow, though, the Star Trek: Deep Space 9 episode "Far Beyond the Stars" left me even colder as its credits began to roll. I'd been dutifully retreating into this show almost every night for several months, mostly because DS9's dark, war-torn take on the Star Trek mythos felt more relatable in 2017 compared to the more-academic Next Generation. Post election, I was a brown person brought low -- but I still had enough energy to wield my righteous anger and so did DS9. But even after binging six grim and often terrorism-obsessed seasons, I wasn't nearly ready for the gut punch of "Far Beyond the Stars."

I couldn't immediately figure out why, but even under that blanket, I was freezing. I started shaking with fear. The afternoon's anemic, wintry overcast light streamed in through my windows and felt too bright for me to stand, so I covered my head with a blanket as the tears and dread overtook me. My chest hurt, as if someone were trying to drill a comically thick screw into my heart, and a series of images whizzed through my brain -- some from the episode I'd just watched, some that were echoes of memories that I'd seen and heard almost every day of my professional life. For the next 20-30 minutes, the end of that episode left me utterly helpless, alone, and incapable of leaving the couch. I wanted to die and disappear.

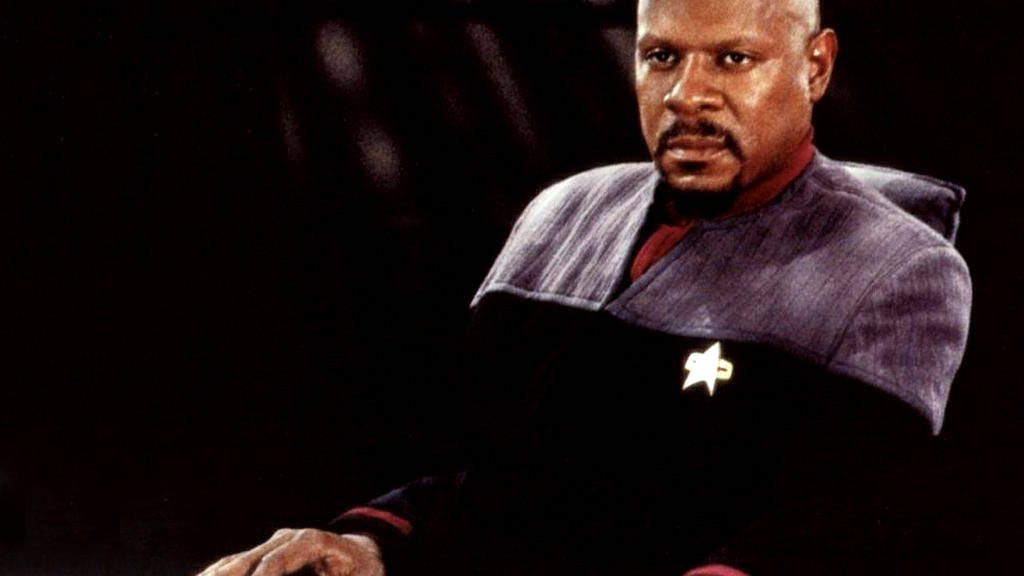

I was having a panic attack triggered by this DS9 episode -- one where the magnetically competent Capt. Benjamin Sisko, (Avery Brooks) is flung into a past where he's no longer a space station commander, but Benny Russell, a sci-fiction scribe writing for pennies per word in the '50s.

Ben Sisko as Benny Russell.

This would be a wholly whimsical and enjoyable sci-fi concept if not for an inescapable reality: Sisko is black, and so is Russell. And Sisko doesn't know he's experiencing this twisted time-travel hallucination, his previous memories as a respected and fearsome captain wiped from his brain. What follows is the story of Russell, the fiction writer completely oblivious to his true identity, attempting to see to publication a story he's obsessed with: the tale of Capt. Sisko of Starfleet. But almost no one in charge of the New York media hegemony of the '50s seems ready to publish the words of a black person telling a story about black people, even in the pages of a sci-fi magazine.

The episode, directed by Brooks himself, further ramps up the drama by casting everyone Russell interacts with as doppelgangers of his DS9 cohort. The badass Major Kira (Nana Visitor) dissolves into Kay, a fellow writer obligated to remain invisible to the readers who don't know she's a woman. The stalwart security chief Odo (René Auberjonois) morphs into a white editor who cagily refuses to run sci-fi stories with black protagonists. And Sisko's son Jake (Cirroc Lofton) breaks bad as Jimmy, a two-bit hustler who dies on the street in front of Russell -- shot by white police officers for allegedly trying to break into a car. At the episode's climax, Russell, overwhelmed by mounting psychological traumas and his failure to publish his story, has a nervous breakdown.

The undercurrent of this episode of DS9, aka the "dark" Trek, is not how far humanity can progress in 300-plus years, but that for all the social progress, hope, and understanding in our future, our racist past is capable of choking us all the same. That the audience knows the grand scale of Sisko's accomplishments throttles the audience to the point, at least for me, of gasping reflexively for air. It didn't matter how competent the future's Capt. Sisko was; seeing his son gunned down over suspicion of trying to steal a car was inescapable. In fact, it's a storyline that represents the opposite of the escapist sci-fi entertainment the entire franchise is known for. The Sisko of DS9 is a skilled mediator, loving father, and an inspiring commander. In "Far Beyond the Stars," all he is is a "Negro with a typewriter." The show that helped me retreat from the reality of people of color dying at the hands of (white) authority figures, then being vilified by a president known for funneling racism like a sewage drain suddenly reflected that reality. The impact of that was so explosive it left me overwhelmed and paralyzed in the spiraling implications of it all for my own world.

"Far Beyond the Stars" written by Ira Steven Behr and Hans Beimler from a story by Marc Scott Zicree, also remains an indictment of our society today. The episode originally aired during Black History Month in 1998 -- about as far removed from the LA riots as the Ferguson riots are from us now in the age of Trump. The business of writing also remains sharply skewed toward specific ends of the racial, economic, and gendered spectra. A recent study from DemocracyFund found that just $71.5 million of $1.05 billion dollars in journalism grants go toward ethnic and racial groups, and that's the largest minority chunk of the pie. As journalist Rachelle Hampton put it for Slate, "As a black woman I didn't have a choice not to go to J-school.... Journalism is an industry rife with nepotism." The halls of magazines and newspapers remain difficult to break into without (white, often male) contacts or mentors. Just from my experience alone, that's often meant policing my own behavior to appear more "white" and less threatening: straightening my hair, cutting my hair, or holding my tongue in meetings when I've heard something unquestionably offensive.

Sisko would never take crap like that, but Russell has no choice. All he can do is try to publish his story, even if it has to be on the terms his white editors. And that's the heart of this episode: what it means to have the agency to write your own story. In the end, Russell agrees to a compromise with his white editor so he can see his story in print. After the chilling police brutality and the segregation and erasure we see earlier in the episode, it's not perfect, but it's something, and Russell is excited for it, giddy even.

In the end, though, instead of publishing a sci-fi story with a black protagonist, the publisher destroys the entire run of the magazine. Russell is devastated. Brooks's climactic portrayal of Russell's workplace breakdown give us his best monologue in all of DS9. It links his character's story to the history of power, and those who wield it:

"I am a human being, dammit. You can deny me all you want but you cannot deny Ben Sisko. He exists! That future, that space station, all those people, they exist in here. In my mind, I created it. And every one of you know it. You read it. It's here. You hear what I'm telling you? You can pulp a story but you cannot destroy an idea. Don't you understand? That's ancient knowledge."

I can't think about that last line without crying. I can't think about it without thinking about what ancient knowledge has been destroyed in the systemic abuse of marginalized peoples. I can't watch that episode without thinking about the times I felt most worthless and undeserving of my jobs as a writer and editor in white-dominant workplaces. I can't watch Russell's plaintive bargaining with his editor over his stories without thinking about times I've policed myself in the process to appear less aggressive, less brown, less assertive, and less likely to cause problems, because of what I perceived as a clear power imbalance. Sometimes that was as simple as pitching stories that a "broad" (read: white) audience would enjoy instead of telling stories I wanted to tell. But other times I had to physically hold myself back or question my own hearing when I heard coworkers and managers using words like "retard," or "cocksucker," or worse. The cost-benefit analysis of staying silent was my continued employment, and I wasn't in a financial position to stand against people who held my career in their hands. That's not an uncommon story, if you care to pay attention, but for people of color or other marginalized groups, it's unavoidable.

I can't hear the doomed Jimmy lament in this episode that he and Russell would "always be n--gers" (the only canonical use of the slur in all of Star Trek) in the eyes of white people without thinking about how I was called a "sp-c" and a "terrorist" high school in the Bush years because of the color of my skin and how my hair grows crinkly when it gets too long. I can't watch Russell's interaction with NYPD detectives without thinking about how I live in Bed-Stuy -- a neighborhood where stop-and-frisk blew up and where I, terrified, was once stopped at 1am for a violation that was eventually thrown out. I can't watch Russell notably wearing a kufi in scenes when he's not around white people (until the end) without considering how uncomfortable I used to get when I was little and my mom spoke in her native, beautiful Brazilian Portuguese when white people were around. I can't watch that episode without thinking that in the end, Russell's attempts to write his own destiny didn't matter. They still broke him in the end, as so many have been broken.

Ben Sisko remembering Benny Russell.

The silver lining is that those efforts did matter, not to Russell, but to Sisko. He wakes up at the end. The doubts he'd had at the beginning of the episode, over whether he might step down from his command and let someone else make "the tough calls," are still there, but he approaches them with renewed resolve. In his present, not even one hour had passed by, despite spending weeks inside the head of Russell. Sisko presses on, because he knows he can't back down when it comes to defending the people of Bajor -- the subjugated planet he is committed to protecting on DS9. I see it as one of the most heroic moments of any captain in Star Trek history: confronted with the erasure of his own heritage, Benjamin Sisko remained defiant.

My silver lining is that I got off the couch. In a teary phone call with my girlfriend, it poured out me in fits and starts: the emotions I'd felt, the paranoia of being stopped or killed by trigger-happy police for making a false move, the anxiety around the injustice against people of color everywhere in America, the shame of being ineffectual and useless in the face of that injustice. As a second-generation Brazilian-American brown person, I don't identify as "black" like Sisko does, but plenty of my relatives would if they lived in the USA. Their history is my history, and the more I considered this broad cultural pain, the more gruesome and oppressive it got.

"It sounds," she offered gently, "like you were having a panic attack." It wasn't the first time I'd heard the term, but it was the first time I'd ever thought to apply it to myself. Looking back, they had happened to me so many times in varying degrees that I think I'd lost count, and the more I thought about it, the more examples I could cite. It didn't happen overnight, but moments in my past when I had felt overwhelmed, or dead inside, or -- my favorite -- like the wolf was at the door, gradually became clear. When that wolf starts to knock, I know who it is at the door before I fling it wide open. I know when it forces its way in to take deep breaths and to try to reason my way through it. My way out of my nightmare didn't reveal itself as quickly or concisely as Sisko's. I had to internalize that which I already knew: I personally, will never be able to fix racism and oppression, but I can control how I move forward from the endless series of aggressions around me.

I am a human being, dammit.

Six months later, I see a therapist regularly, largely to talk about my feelings, something that sounds like a cliche but is really a product of how much I've bottled up and held in every day of my life. I've had panic attacks since then, but I handle them better. In its own way, "Far Beyond the Stars" helped me set a rubric for them, to know that they have a prior trigger in my life, to recognize the world's problems are not inextricably linked to my reactions to them. No matter how big or small, it would be Capt. Sisko's job to keep his cool and get his crew out of danger. It's my job to do the same for myself, to stay alive, to do the hard work of working on myself, especially when it feels like it'd be easier to die or disappear.

And in the end, there's no hiding. There's only one thing I can do, in the words of Sisko: "Stay here and finish the job I started."