On 'Sharp Objects' and Feeling Ruined

Watching Camille struggle to survive both her past traumas and the problems she's developed in reaction to those traumas, I've been forced to face some similar demons of my own.

Scars are like corporeal cartography, mapping out the most painful experiences we've survived. But what about scars from cuts intended to cure pain? What tales do they tell?

I have a secret history of self-injury. Like so many "secrets," though, my self-injury scars merely hide in plain sight - more ignored than concealed, really. They're permanent reminders, inscribed in skin, of both my desire to control my feelings and my difficulty doing so. Self-injury was always a reaction to taking in too much - times when something so bad happened that feelings of shock or shame spun beyond my subjective control and into the timeless territory of trauma. That's what trauma is: extreme, excessive overstimulation a person cannot integrate into their sense of self. The overstimulation produces a wound that affects the whole psychic memory system; trauma injures our sense of identity and demands some form of release. Anytime I reached for a knife it was because I was overwhelmed, unable to process an event. Usually I was also hiding my rage about the source of that trauma - a rage I was deeply ashamed of and unwilling to express openly. So instead I opened myself up.

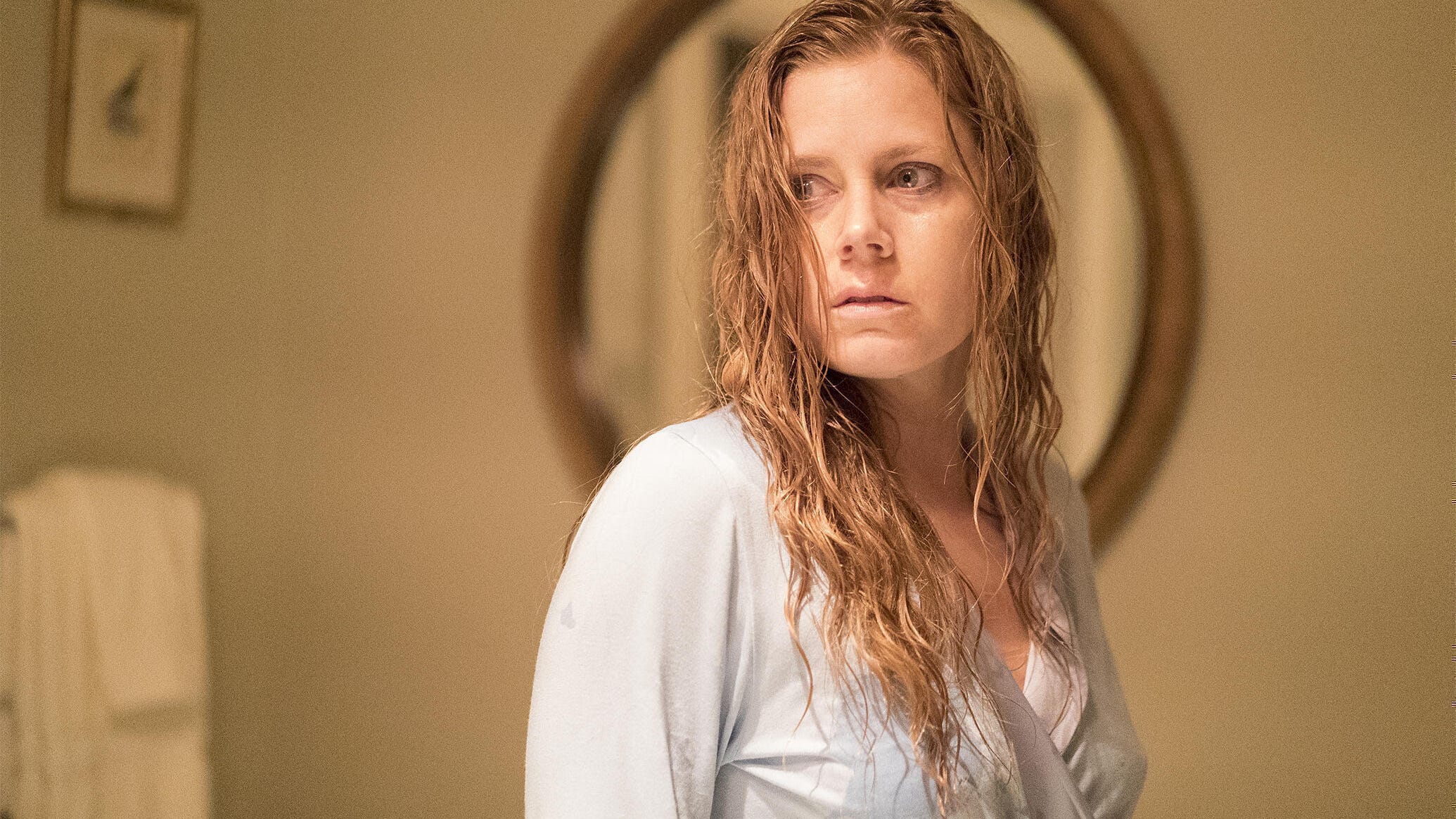

Sharp Objects, the HBO show created by Marti Noxon (based on the novel by Gillian Flynn, and directed by Jean-Marc Vallée), offers audiences a rare opportunity to reflect on how and why we hurt ourselves. Hypnotically beautiful yet powerfully disturbing, the eight-episode miniseries presents Camille Preaker (Amy Adams), a journalist out of rehab who reluctantly returns to Wind Gap, Missouri - Camille's hometown, ruled by her cruel and narcissistic mother Adora (Patricia Clarkson)- to investigate the killing of adolescent girls. Sharp Objects explores an exceptionally woman-centered vision of the dead-girl TV trope, and showcases standout performances from Patricia Clarkson and Amy Adams. Even more unusual, it features an unconventional woman protagonist whose struggles with what doctors call NSSI (non-suicidal self-injury) disorder are actually relatable. Camille suffers from dizzyingly intense PTSD caused by traumas seen only in snippet form, and seeks relief through extreme alcoholism and self-injury. Watching Camille struggle to survive both her past traumas and the problems she's developed in reaction to those traumas, I've been forced to face some similar demons of my own.

Non-suicidal self-injury is not often discussed. But although a taboo topic, NSSI does serve a function: self-injury is a form of self-medication and mood regulation (pain releases mood-elevating endorphins, for example). NSSI most often occurs in adolescents and young adults, beginning around age 12-14. Cornell University notes self-injury rates of 17.2% in adolescents, 13.4% in young adults, and 5.5% in adults. Often preceded by childhood trauma, NSSI also frequently occurs alongside other disorders, particularly PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, borderline personality disorder, and eating disorders.

Depictions of NSSI on TV are infrequent; even less prevalent are subtle, sympathetic representations that productively explore the relationships between self-injury, sexuality, and female subjectivity. This is important, because although statistics show that people self-injure regardless of race (the unbearable whiteness of TV representations notwithstanding), gender, or socioeconomic status, women who were mistreated as children - and particularly those who were sexually abused - are more likely to turn to NSSI than are men who were similarly exploited as children. Perhaps most significant to the development of NSSI disorder is what researchers call "body objectification." The theory is that "when people see their own body as an object - the result of internalized cultural and familial pressures - it's easier to distance themselves psychologically from their bodies and hence to harm themselves." Finally, sexual minority status may also increase the incidence of NSSI, with bisexual women most at risk: one 2011 study found that up to 47% of bisexual women have self-injured. These are serious statistics, yet when NSSI is referenced on TV it's usually as a punch line, a way to dismiss a character. Obviously this perpetuates the social stigma around self-injury, and - more generally - around mental illness as well.

Watching Camille struggle to survive both her past traumas and the problems she's developed in reaction to those traumas, I've been forced to face some similar demons of my own.

But TV representations intended to be sensitive aren't always relatable, either: despite the diversity of the NSSI profile, portrayals of self-injury tend to be reductive, relying on unrealistic caricatures that obscure more than they clarify. Characters who self-injure are often either so deeply dysfunctional, or so incredibly high functioning, that those of us who live between these binaries never see ourselves represented. I still vividly recall an old House episode where the young patient, a "Type A" CEO with congestive heart failure, turned out to be a secret bulimic and cutter. While I shared her core psych symptoms - withholding pain, desire for control, and shame - her extraordinary levels of discipline, success, and wealth made her harder to relate to. Basically I came up about a million dollars short.

Even less relatable is Skye Miller (Sosie Bacon), a character from the controversial Netflix series 13 Reasons Why who also self-injures. A high school student nicknamed "Twilight" by classmates, Skye shares Camille's gift for sarcasm and preference for a uniform of black on black on black. But the resemblance ends there. Admittedly, Skye is a compelling character, sympathetically portrayed by Bacon. But she's also a stereotype: a depressive, subcultural placeholder whose didactic function actually limits our understanding of self-injury. For all its attempted "realism" 13 Reasons Why offers remarkably little context for mental anguish, or the dangerous things we do when we're in too much pain. Where Sharp Objects tells ugly truths about a violence that begins at home and never truly ends, 13 Reasons Why circles obsessively around trauma but then tries to comfort audiences with fantasies of rescue and redemption. Take the 13 Reasons Why episode "The First Polaroid," for example, where protagonist Clay Jensen (Dylan Minnette) is so determined to help Skye with her NSSI disorder that he proposes 24/7 crisis availability, hourly texts, reminders to use the rubber-band method or try meditation, and offers of "mindfulness walks." Predictably, this episode - with its idealistic image of a knight in shining armor saving a damsel in distress - was written and directed by men (based on a book by a man). 13 Reasons Why also misleads viewers when it shows Skye insisting that self-injury and suicide are oppositional: in fact NSSI is a strong predictor of later suicide attempts.

Patricia Clarkson and Eliza Scanlen, Sharp Objects

Anne Marie Fox/HBOUnlike 13 Reasons Why, Sharp Objects offers no easy solutions. For me this means that Sharp Objects is more painful to watch, but also more rich and rewarding, than other representations of self-harm I've seen. Camille - a former cheerleader and town princess, and now an adult in her 30s - is not necessarily the kind of character people imagine when they picture self-injury. And yet her experiences of familial mistreatment and childhood sexual trauma are exactly commensurate with the clinical picture of NSSI, which suggests that many of us who have self-injured may actually see an aspect of ourselves in Camille. Her crisis is both subtler and more severe than that of a character like Skye, whose problems with NSSI - not to mention her preference for black clothes and eyeliner - seem to simply vanish after a stay in a cushy rehab facility and a shiny new diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Sharp Objects skips 13 Reasons Why's graphic depictions (which research shows can do more harm than good, anyway) to instead focus on something often sorely lacking in TV: a nuanced narrative of the traumas that shape us, and the mental states surrounding self-injury. In the episode "Closer," Amma (Eliza Scanlen) - Camille's younger half-sister - recounts to Camille that she has a friend who cuts herself. Amma says the friend claims: "it doesn't hurt, because the cuts are already there ... the knife just lets them out." Camille dismisses this interpretation, remarking derisively that Amma's friend "sounds like an after school special." The unnamed cutter actually has a point, but the emo pronouncement is an affront to Camille's hardened sensibilities. Focused on survival, she is utterly unable to be vulnerable with others in the ways that self-harming teens on TV often are. Camille's comments can be almost as cutting as those of her mother Adora; though not an unkind person, Camille is hard on others because she's hard on herself. She has a stoniness sedimented by intergenerational trauma. Camille's impenetrability and her deliberate penetration of her own flesh are inextricably intertwined. And whereas 13 Reasons Why relies on shock effects that are as transient as they are traumatic, Sharp Objects forces the viewer to sit with their discomfort indefinitely - just as Camille will have to live with her scars forever.

My demons aren't even remotely conquered; they're just mildly concussed.

I can't relate to most TV representations of women, much less women who self-injure. But I do identify with Camille - a writer who looks "normal" but cuts herself, who carves words like "BAD" and "A DRUNK" into her desk and "LIAR" onto the surface of her black jeans. For those of us who hide profound private pain but pass as expected to the external world, self-injury can be an attempt to unify the internal and the external. Finally our outsides can be as injured, as "ruined" (to quote Adora and other mothers) as our insides already felt. Like Camille I exist in a very real but largely ignored grey zone, too high functioning to be institutionalized but not high functioning enough to completely sublimate my trauma into the kind of exaggerated overachievement spotlighted on dramatic TV. Struggling to write, struggling to tell the truth about myself and my history, but mostly just struggling to survive, in Camille's presence I am haunted by my past self. I also see the past selves of other women I've known - women whose stories don't usually make it onscreen.

Honestly, watching Sharp Objects was harrowing at first. It's been over ten years since I cut myself deliberately, but I still feel ruined sometimes. And Camille's catastrophes felt contagious; the show pulled me back to a dark and painful place I'd tried to bury under better memories. But in this case, wrestling with repressed demons wasn't a damaging process. It was healing. Camille revived a part of me I'd tried to abandon, and for the first time ever I was ready to care for that sad and angry girl like a long-lost friend.

At one point in Sharp Objects, when a character tries to congratulate Camille on how well she's conquered her demons, Camille responds: "my demons aren't even remotely conquered; they're just mildly concussed." Rarely have I so related to a character or line of dialogue. Do I hope to move beyond merely concussing my demons - to move beyond survival and into a happier, healthier, more honest life? Of course I do. But in the meantime, do the struggles of a character like Camille validate my own experience that people who look okay may not be, that ugliness can feel truer than beauty, and that friends and family can't always be there to support you? Absolutely.

Like any good work of art, Sharp Objects offers more than merely catharsis. Seeing a well-crafted and contextualized story about trauma and self-harm also reminded me that I have agency over my own stories. I am more than just what has happened to me - or even what I've done to myself. My past pain does not define me, and my future happiness is an unknown quantity.