How Straight Fictional Women Shaped My Gay Identity

Instead of turning to characters who represented my community, I found solace in women like Meredith Grey and Alicia Florrick.

All I remember from leaving my childhood home in Ottawa for a new life in Seattle was the bright opportunity to befriend Seattle Grace's Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) and Cristina Yang (Sandra Oh). In my 13-year-old mind, the move would bring me 2,574 miles closer to achieving the depth of connection their friendship had after eight seasons of Grey's Anatomy. Of course, my move across the continent would prove disappointing in that regard (Grey's is filmed on a soundstage in California), but it marked the beginning of my search for a sense of belonging through female characters I followed obsessively on television.

I mostly steered clear of queer people during my high school years, which were spent in an aggressively traditional setting straight out of a diluted scene from Mean Girls. Confused and lost in my own identity in a country where gay marriage was still illegal, I had little to no chance of understanding the spectrum of sexuality and my place within it. I couldn't quite assimilate to high school masculinity, and any emotion I expressed outside that narrow definition was heavily taunted, accosted, probed. I heard faggot whispered and yelled from every direction, sometimes even from myself in a bid to shift attention and melt back into the background. I'd survive the day, and then when I got home, I'd turn on the television to see...Glee's Kurt Hummel (Chris Colfer): flamboyant, annoying, and like many gay men on television, burdened with the heavy narrative load of homosexuality. As a teenager, the gay, male characters I saw on TV were so binary: feminine or masculine? Out or closeted? Into fashion or not into fashion? Either they embodied and attempted to redefine a stereotype or rejected it altogether, opting instead to "reclaim" traditional masculinity for gay men.

In the aughts, gay men were rarely the protagonist; they were often written in briefly in the service of lead characters' storylines (and frequently written out via death), or included specifically for a "very special episode" on sexuality.

There were exceptions, of course, but you had to search for them, which was difficult in a pre-streaming era, especially considering most teens at the time didn't get personal laptops until college. True Blood's Lafayette Reynolds (Nelsan Ellis) stands out as a rare outlier, a southern Black gay man who went beyond binaries and gender in his self-presentation. Muscular and strong but covered in eyeshadow and wearing large hoop earrings, the character was a genderf--- worthy of further praise. Lafayette, while expressing a femme aesthetic, was a stark difference from characters like the effeminate and judgmental Stanford Blatch (Willie Garson) on Sex and the City. I was disappointed when I found an interview from early in the series and realized Ellis himself was heterosexual, his voice a few octaves lower than his character's. Of the shows I actually had the ability to watch, I only saw gay men reflect stereotypes I didn't want to be. Of the shows that were doing brilliant queer work on channels I'd never be able to get away with watching with my parents in the living room, I saw straight men step into my space.

Unable and uninterested in relating to the limited range of masculinity on television, I turned to female characters. Meredith and Cristina's friendship reflected my own ease and effortlessness with the people closest to me. Their love for each other is rarely spoken out loud but is implicit in their dance parties and heart-to-hearts. They aren't held back by societal burdens. They are not bullied or called faggots or made to wear identifiers that they didn't choose. On top of being the narrative center of the show, they embrace competition and rarely question if they belong to the world or not. Though medical surgery was not likely an option for my own career, I felt more connected to the nuance in their lives and the catharsis from the dramatic proclamations of love in scrub rooms and back-door relationship gossip than I did anywhere else in my media consumption (I was too closeted to watch gay blockbusters like Brokeback Mountain, and I'm not mad I still haven't seen it). Through their quirks and misgivings, their friendship always allowed them the space to be fully realized people. These women could transcend their failures and what other people thought of them, and I wanted a piece of that journey for myself.

There is obvious precedent for gay men finding empowerment through a canon of gay icons, most of them (typically straight, white) women celebrities: "stanning" culture has built the foundation of careers across generations (Donna Summer to Madonna to Julianne Moore to Carly Rae Jepson). These relationships are continuously dissected, declared problematic, and reassembled in criticism and cultural discourse. And while I have my own shortlist of female stars that "give me life," I find my solace mostly in fictional women like Meredith and Cristina. These female characters held the space I was desperately seeking as a lonely, depressed student, hungry to feel some kind of agency and freedom--even if it was just with one other person--in my day-to-day life.

Television studies scholars have theorized the soap opera genre offers continuous character development that bring viewers in conversation with its world-building. In other words, how could you not get attached to characters that appear on TV three times weekly? Not quite a soap opera, Grey's Anatomy still manages to showcase around 24 episodes per season, and 15 years later, I still feel deeply connected to the history between Meredith Grey and me in a way that doesn't cross other genres. I have seen Meredith survive more traumas than any person could ever endure, and return to her career and life with the perseverance to find joy and happiness. When Meredith almost loses herself in the icy Seattle waterfront, she comes back from the brink of suicidal ideation to build a loving found family. She chose life from the depths of despair. I too, have almost lost myself in the icy waters of major depression while hiding in the shadows of my authentic self. The temptation to let myself sink and stop waking up in the morning is palpable, and has been since I was a child. But the more I choose authenticity, the further I surface, and decide I am also deserving of love, joy, and happiness. Meredith is still at the hospital, fighting for the life she has created, fighting for her right to love. Time and time again, the catharsis of that strength awakens me to my own agency to access my tools for survival (medication, therapy, connection). Through hundreds of episodes and 15 years, we have a special bond, her and I.

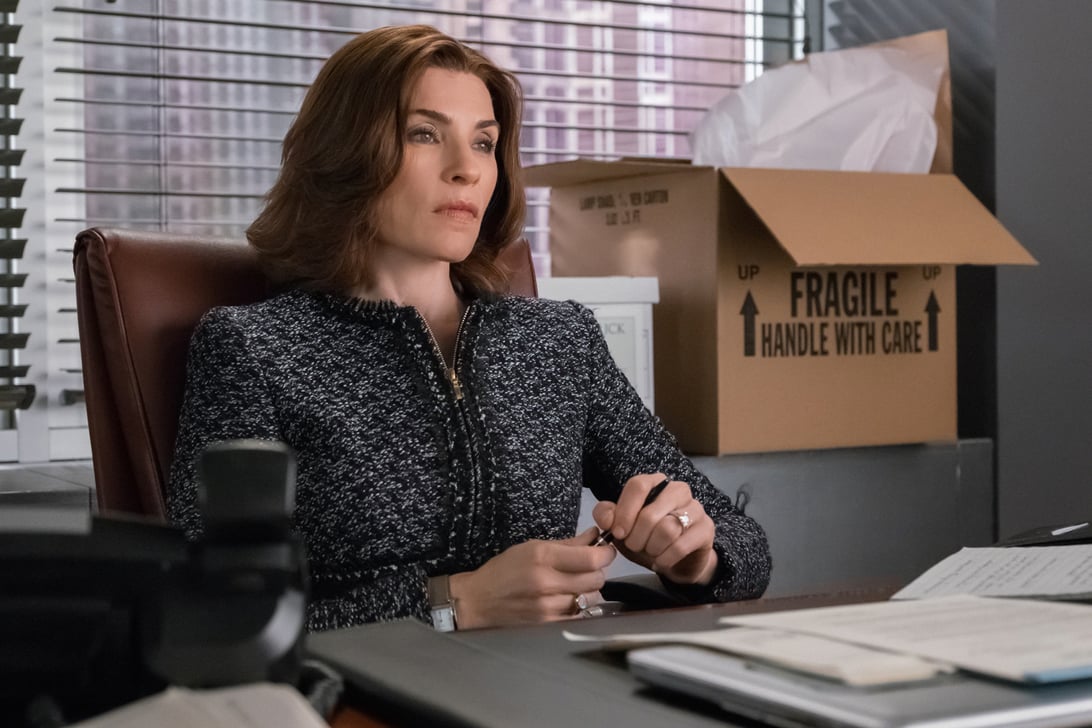

While Meredith was my first love, she wasn't my only. Approaching the end of high school, I watched Eliza Dushku play a different character weekly as a programmable human on Joss Whedon's Dollhouse, Erin Karpluk travel through time (as therapy!) to re-examine her life problems as Erica Strange on Being Erica, and Julianna Margulies rebuild her life as a first-year legal associate in The Good Wife. Like viewers of the soap opera, I became indebted to the attachment that happens when you watch these protagonists consistently: personhood, friendships, and relationships evolve over seasons rather than the standard and short-term narrative arc of a film. These women barely place in the pantheon of gay icon culture, but were at the top of my personal list because like me, they were committed to living in their own skin even when their narratives wore them down to nothing.

Entering the 2010s, I began feeling more and more comfortable with my sexuality and all of its possibilities. By the time I came out to my parents, I had fully owned my truth. The fictional narratives and female characters that had shaped my coming-of-age gave me the strength to access this vulnerability. The Good Wife was in its third season when I came out, and Alicia Florrick finally began finding a foothold in her career and self-identity beyond the very public sexual misconduct of her husband. At her most measured and confident (plus a new haircut), she shot down the opposition in court with precision and gusto. I channeled her energy in the awkward sit-down with my parents, and prepared myself for the cross-examination. As "I'm gay" came out of my mouth, I was as surprised as they were--that like Alicia, I had found myself willing to run headlong into risk to be myself rather than watch my own life pass me by from the sidelines.

That said, these incredible heterosexual (mostly white) women only got me so far. My brutal and continuous battle with depression and anxiety often festered into a deep loneliness not even Meredith Grey could cure. But still, the emotional complexity of female characters on the small screen offered me an alternative to the more static, hegemonic representations of manhood on serialized television. These women are often indulging in the complex and messy inner world of emotion and vulnerability in a way I didn't feel I was allowed and certainly didn't see anywhere else in pop culture. These women had little to teach on my day-to-day tribulations as a queer Arab French-Canadian millennial, but were instrumental in creating the blueprint for dealing with my own messiness. Above all, with these women (and those in my real life), I felt belonging I couldn't seem to find anywhere else.

Thankfully the television landscape has changed drastically: from shows like HBO's Looking toHow to Get Away With Murder to The Other Two, it feels like a there's a queer revolution to watch in every streaming cycle. And despite these shows' shortcomings, queerness is being unpacked as a much broader, more nuanced idea than ever before. In 2019 alone, I watched three "straight" characters fall for women on the most recent seasons of Broad City, You're the Worst, and Better Things. I yearn for the day when it becomes commonplace for male characters assumed as straight to explore their sexuality in the same way, and for blueprints I craved as a teen to be so ubiquitous they aren't thought of as blueprints at all. But until then, I have Meredith Grey to remind me how rewarding it is to be myself.

Michel Ghanem is a PhD student in Communication & Culture at Ryerson University in Toronto. To support his work and research, subscribe to his newsletter and follow him @wtfmichel.